| From the September 2000

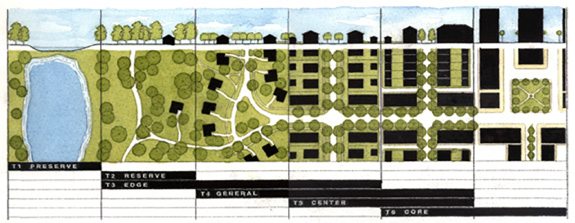

issue of New Urban News "Transect" applied to regional plans The Transect, a new model for planning and coding the New Urbanism, is beginning to be employed in regional planning. Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company (DPZ) recently used the Transect as the basis to create a plan and code for Onondaga County, New York, which includes the City of Syracuse and surrounding suburbs, villages, and countryside. A regional planning effort by Torti Gallas & Partners, completed in March, 2000, was based entirely on the Transect. Developed by Andres Duany and DPZ, the Transect is a categorization system that organizes all elements of the urban environment on a scale from rural to urban (see diagram below). Its potential lies in: 1) Education (it is easy to understand); 2) Coding (it can be directly translated into zoning categories); 3) Creating “immersive environments.” An immersive environment is one where all of the elements of the human environment work together to create something that is greater than the sum of the parts. The Transect has six zones, moving from rural to urban. It begins with two that are entirely rural in character: Rural preserve (protected areas in perpetuity); and Rural reserve (areas of high environmental or scenic quality that are not currently preserved, but perhaps should be). The transition zone between countryside and town is called the Edge, which

encompasses the most rural part of the neighborhood, and the countryside just

beyond. The Edge is primarily single family homes. Although Edge is the most

purely residential zone, it can have some mixed-use, such as civic buildings

(schools are particularly appropriate for the Edge). Next is General, the

largest zone in most neighborhoods. General is primarily residential, but more

urban in character (somewhat higher density with a mix of housing types and a

slightly greater mix of uses allowed).

The plan illustrates how the Transect classifies the elements of the human environment from rural to urban, in a left-to-right sequence. At the urban end of the spectrum are two zones which are primarily mixed use: Center (this can be a small neighborhood center or a larger town center, the latter serving more than one neighborhood); and Core (serving the region — typically a central business district). Core is the most urban zone. “The “Transect zoning” concept should be the new paradigm for local land-use regulations, not the least of all because it can be implemented through the familiar legal framework of Euclidian zoning districts,” says Bill Spikowski, a planner in Fort Myers, Florida, who has applied Transect concepts in his collaborative work with Dover Kohl & Partners. “This time around, though, the zoning districts should be keyed to the desired Transect zones (edge, general, center, and core), plus those unavoidable, auto-dominated zones for heavy industry and big boxes.” Duany, who previously put forward the Lexicon of the New Urbanism as a universal standard for designing neighborhoods and towns, has since changed his mind. He now touts the Transect, originally embedded in The Lexicon, as the true standard. “I am convinced that the Transect will do the job, not The Lexicon as we thought,” he says. “The Lexicon has advocates, but I have come to realize that it is wrong. The Lexicon is too specific and complete to be a standard. The real matrix, I believe, is the Transect.” Onondaga County, New York DPZ created specific plans for seven study areas in the 800 square mile county. These areas represent every part of the Transect — from the inner city to the countryside. The specific plans have already inspired two new urbanist projects, one of which has broken ground. Some of the other theoretical plans — in particular a plan to turn the closed Fayetteville Mall into a town center — have garnered interest from developers. Like other new urbanist planning efforts, the Onondaga plan is based on the idea that “The basic increment of planning is the transit-supportive, mixed-use neighborhood.” The plan and the accompanying codes are innovative in that they are geared to the zoning categories of the Transect. In addition to the Transect zoning categories, the Onondaga codes have a mechanism for “civic overlays” to introduce parks and civic buildings in neighborhoods. Finally, special-use districts are included for developments that fall outside of the provisions of the code. Districts that follow the “general intent” of the code — e.g. a college campus — would be given a waiver. Districts that do not follow the intent — e.g. an industrial campus or big box store with parking in front — can be granted as exceptions through negotiation. Each of the Transect zoning categories — Rural, Edge, General, Center, Core — has detailed provisions for density, thoroughfare dimensions and design, block dimensions, the design of parks, appropriate building frontages, the mix of uses, building design, parking, and other aspects of the human environment. In some respects, the Onondaga code is far more detailed than conventional suburban zoning. For example, instead of just being asked for a percentage of “open space,” the developer may be required to build a square, green, or plaza. No architectural style is mandated, but DPZ does suggest detailed requirements for frontages, facades, roofs, eaves, and other building elements. In other respects, development options and freedom increase with the new code. Under conventional zoning, a developer with 100 acres may have no choice but to build one kind of residential at a consistent density. Under the new code, the developer could opt to build a village — with the developer deciding how much of the project would be designated Rural (0 to 30 percent), Edge (10 to 50 percent), General (30 to 50 percent), and Center (30 to 50 percent). All of these zones have options in terms of thoroughfares, building types, frontages, civic spaces, and other elements. The code ensures that each zone is immersive — i.e. all of the elements reinforce each other to produce a specific character. Once the Onondaga code is completed, it will be available for adoption by all of Onondaga County's 35 municipalities, who can tailor it to suit their needs. The code actually has two parts — one for infill and another for greenfield. Karen Kitney, director of planning for Syracuse-Onondaga County, expects the code to be accepted in its final form in late fall. At that time, copies of it may be available for purchase by planners outside of the county. Albemarle County, Virginia The Transect helped participants get over their reflexive fear of mixed-use development, says Neil Payton, lead planner for Torti Gallas on the project. “When you talk about mixed use, people imagine a high-rise building or a Food Lion next to their house. But when you show them what it looks like at an appropriate scale and density, they say ‘yeah, I would like that — I didn't know that was what you meant.' ” The next question, says Payton, is “how do you code” the scale and density. “The Transect was the key to getting a lot of light bulbs to go off in people’s heads, to allow them to see how it would work,” he adds. Torti Gallas explained every aspect of the Transect, applying it to theoretical scenarios. The outcomes were drawn and compared to conventional suburban development. “While seemingly radical at first, its ultimate familiarity to them was so potent, it was easy to take the next step, a methodical analysis of current policy and regulation and a proposal for wholesale replacement,” says Payton. “What is also interesting is the consensus that was reached between developers, builders, lenders, Realtors, environmental activists, neighborhood activists, architects, planners, landscape architects, rural conservation proponents, and affordable housing specialists.” Payton says the Transect organizes the process of urbanism into a system. “It represents the standardization that urbanism lacked, but the building industry always had.” However, Payton does not expect this concept to be embraced by everybody, especially municipal planners. “It’s so simple, it is viewed by some suspiciously — yet that is the elegance of it.” Albemarle County planner Elaine Echols says, at first, the Transect was “very confusing, and hard to grasp” for the participants in the Development Areas Initiative Project. Although the advisory committee supported the Transect concept, she doesn’t believe that it was the most important factor in achieving consensus. “Envisioning something better than what we have right now was the key to getting them together on this.” |