West Onondaga |

|

|

West Onondaga Street was once one of Syracuse’s grandest thoroughfares, lined with Italianate and Queen Anne style mansions designed by Syracuse’s most prominent architects, including Archimedes Russell and Charles E. Colton. Some of these structures, such as 515 West Onondaga Street, are already listed on the National Register of Historic Places as individual sites. West Onondaga Street was, for a long time before the opening of interstate route 690, the gateway to the city from the west, a resplendent elm-lined drive (the New York State Republican party was organized beneath one of these elms in 1856). In 1879 the street was advertised as “second to none.” West Onondaga Street experienced its Queen Anne heyday during the latter part of the 19th century, and the street continued to flourish during peak years of Syracuse’s growth, from 1890 - 1930. Trinity Episcopal Church of Syracuse was built to serve the wealthy elite of West Side and to further embellish the street with monumental architecture.

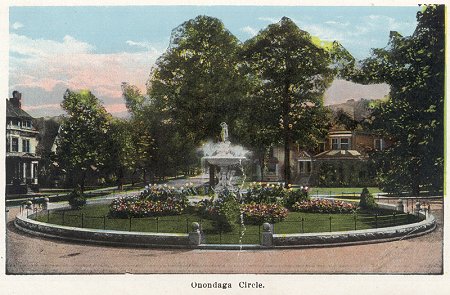

Even in the 1940s, the street maintained its grandeur. A 1942 article in the Herald-Journal wrote “it was the style of the times to build a house in which the individual could exhibit to the world that it was in his power to spend money. No neighborhood in Syracuse exhibits this quite so well as the 500, 600 and 700 blocks of West Onondaga Street.” Perhaps the writer exaggerated a bit. For many, James Street on the East Side of the city remained the luxury artery par excellence. Apartment houses were erected, and older residences were cut-up as boarding houses. Demolition of poor downtown and east side neighborhoods for “urban renewal” caused a shift of low-income into neighborhood. The street became increasingly run-down. Some old houses were demolished and new infill low-income housing complexes were erected, almost all architecturally unsympathetic to the historic character of the street. The poor appearance of the neighborhood deterred more extensive redevelopment, however, despite proximity to downtown. Unlike James Street, West Onondaga was considered too risky for white-collar office development. Today, however, we cannot judge, as most of the mansions on James Street were demolished in the 1960s and 1970s. West Onondaga was spared that fate, though its building fell into terrible disrepair. Some have been lost, a few have been restored. The majority – like the fate of this once-great street itself – are in the balance. The character of the street is changing again. Since 1989 more old houses are being maintained, and a few have been reclaimed as residences. New commercial development, however, such as a large Rite Aide threaten to introduce a strip like appearance, with low box-like stores and lots of up-front off-street parking. Several organizations including the West Onondaga Street Alliance, are making a concerted effort to improve the quality of life on the street and restore West Onondaga’s historic character. History Today it is simple enough to get from South Clinton Street to South Ave, but before 1830, travelers trying to traverse the area would have found themselves in the midst of a large swamp. It is said that West Onondaga Street started out as Cinder Road, so called because a man with a horse cart put down cinders all the way to the edge of Elmwood Park to create an access road to Mickle’s Foundry, a producer of arms for the War of 1812. When the swamp was drained in the 1830s, the area was opened for residential development. Before long, a number of Greek Revival mansions shaded by elm trees lined the street. Henry West Slocum, a local attorney, lived on the northwest corner of West Onondaga Street and Slocum Avenue, then called Russell Avenue. He entered the service as an artillery captain during the Civil War. By 1864, Slocum was promoted to major general and participated in Sherman’s famous march from Atlanta to the sea. The Greek Revival home of Syracuse’s first mayor, Harvey Baldwin, stood on the northwest corner of West Onondaga and South West Streets. During the later part of the 19th century, the area was favored by well-to-do Syracusans who liked to live in Queen Anne homes and occasionally made do with a Second Empire or a Richardsonian Romanesque-inspired residence. |

|

|

Whelan Brothers Funeral Home 366 West Onondaga The Onondaga Apartments The 400 Block Gillette Residence Trinity Episcopal Church Trinity Parish House Republican Party Marker Fairchild & Meech Funeral Home Gillette Residence 600 Block West Onondaga Barnes Residence 636 West Onondaga Street

|

Holden Residence 643 West Onondaga Street Hendricks Residence W. L. Smith Residence 658 West Onondaga Street Whedon Residence The Harriet Baum & William Neal House

Alexander T. Brown House Hurlburt Smith Residence Gridley Residence Nathan Breed

Residence

Centenary Methodist Episcopal Church |