How Syracuse Built the World's Tallest SkyscraperOutside of New York City, In Seattle |

|

Smith Tower under construction - 1914. When the 42-story Smith Tower opened in Seattle in 1914, only three buildings in the world were taller -- and all of these were in New York City . The tallest in the world at that time was the 60-story Woolworth Building (to put this in perspective, the tallest building in Syracuse is still the 1928 State Tower at 22 stories). Although the terracotta and steel Smith Tower has long been Seattle's favorite skyscraper, it was financed by -- and named after -- Syracuse industrialist Lyman Cornelius Smith and designed by Syracuse architects Gaggin & Gaggin. The story starts several years earlier. In the mid-1880's, in Syracuse, the L. C. Smith shotgun factory was selling about 5,000 guns a year. Smith loaned his mechanic, Alexander Brown, to another company to help them with the design and manufacture of typewriters. Brown returned from this experience with his own design for a typewriter incorporating two separate keyboards for upper and lower case letters. This "Smith Premier" was the first typewriter Smith brought to market.

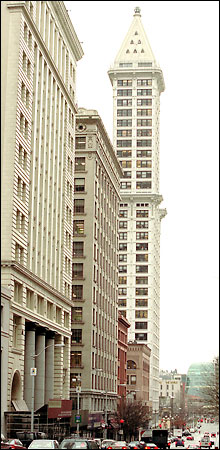

Smith Tower today. In 1900 Smith donated funds to Syracuse University for construction of the new Lyman Cornelius Smith Hall. This structure was to house the new Lyman C. Smith College of Applied Science, offering degrees in Civil, Electrical and Mechanical engineering. The architectural firm of Gaggin and Gaggin was chosen for this project. In 1903, Smith sold his gun business and took the leap into typewriters, opening a new factory at 701 East Washington Street. The gamble paid off handsomely and the Smith Typewriter Co. of Syracuse became one of the nation's largest typewriter manufacturers. It eventually merged in 1926 with the Corona Typewriter Company to become Smith Corona.When Lyman Smith visited Seattle in 1909 it was known as the "fastest growing city in America," and Smith wanted in on that growth. He decided to create a building that would be so tall and so distinctive it would not be exceeded in either way during his lifetime. To design such a building he commissioned the Syracuse firm, Gaggin and Gaggin. Smith did not live to see his new building completed, but it is likely he would have been pleased. The day it opened, 4,400 visitors rode to the 35th-floor observation area for 25 cents apiece and marveled at the "aeroplane views" it afforded of the city, Puget Sound and the forests and lakes beyond. The building's promoters boasted that one could tour its 42 stories and 600 offices, pass through any one of its 1,432 steel doors, gaze at the spectacular view through any of its 2,314 bronze-encased windows, while still feeling confident that the 500 foot high edifice stood secure on 1,276 concrete piles reaching 50 feet below ground to bedrock.

A skeleton of structural steel was built atop those concrete piles, then wrapped in a skin of terra-cotta. The Seattle Times said of the completed frame, "the monster structure acts as a guiding beacon to vessels in and out of Elliot Bay... The Queen City's noblest monument of steel is declared by seasoned skippers to be by far the finest aid to navigation ever placed on Puget Sound." According to Skyscraper.com, steel for the structure was manufactured by The American Bridge Co. in a Pittsburgh plant, then shipped to Seattle on 164 railroad cars each carrying about 28 tons. The severe (7.1) earthquake of 1949 caused so little damage to the building that the greatest expense was the fee for the investigating structural engineers. The 605 foot Space Needle, built for the 1962 World's Fair, became the first Seattle structure to exceed Smith Tower in height. Other taller office buildings were soon to follow and, as they did, the center of downtown shifted northward along the edge of Puget Sound. Not only was the once cutting-edge Smith Tower no longer the most coveted address downtown, it was no longer in downtown. With time, the building became known as home for many of the city's non-profit organizations who relished the building's history, style -- and low rents.

Smith Tower got a new lease on life in 1995 when it was purchased by a developer for the bargain basement price of $7.6 million. The firm then invested more than $27 million in renovations including state-of-the-art fiber-optic cabling, air-conditioning, even new uniforms for the elevator operators (Smith Tower retains what are reportedly the West Coast's only manually operated elevators -- eight brass-caged beauties). Its 35th-floor Chinese Room, an elaborately decorated space popular for weddings, is surrounded by an observation deck where visitors can still take in magnificent views of downtown. With its face lift, Smith Tower was once again one of the most sought after addresses in town -- particularly among the new "dot-com" businesses. The non-profits left and new tenants arrived including Walt Disney Internet Group (which took seven floors), ESPN.com and Tidemark Solutions. With the recent recession, many dot-com businesses have fallen on hard times. The result has been growing vacancy rates throughout Seattle -- particularly in Smith Tower. Senior property manager, Alex Bennett, isn't worried. In late 2001 he told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer that, with its mosaic floors, brass elevator cabs and carved wooden Indian heads in the lobby, the building has remarkable character. Although the rent has skyrocketed, Bennett said there will always be tenants that are drawn to the magic of Smith Tower. "It is not uniform in any way; you are in something that is alive," he said. "And when you are in a space like that, it is more comfortable; it is more dynamic." Sources:

|