HISTORICAL BACKGROUNDSyracuse University Campus

Excerpted from Syracuse University Campus Plan 2003

PREFACE Syracuse University's founders understood the built environment's power to shape the academic experience. When Bishop Jesse Peck, the first chairman of the Board of Trustees, developed his General Outline of the plan of Buildings for the University, he set forth the concept of an eclectic campus to reinforce his vision of a university grounded in an expansive, humanistic view of the world. While times and objectives have changed, the University has continued to honor Bishop Peck's belief that the campus should be a mirror held up to the academy and its aspirations. ROOTS

The University's ancestor, Genesee College, was chartered in Lima in 1849; its trustees' desire to relocate to Syracuse was realized in 1870 with the chartering of Syracuse University.

|

Syracuse University has its origins in the Genesee Wesleyan Seminary, an institution founded in 1832 by the Genesee Methodist Conference in Lima, New York, south of Rochester. Seven years earlier, central New York had been transformed by the completion of the Erie Canal, and the territory it traversed was proving to be fertile ground for economic, cultural, and educational innovation. Religious movements like Methodism flourished, prompting the creation of new institutions. The builders of those institutions viewed themselves as inheritors of the republican virtues embodied by Classical Greece and Rome. That belief, refracted through a prism of Yankee pragmatism, manifested itself in the region's physical and intellectual landscapes. The Genesee Seminary was founded by a group of circuitriding Methodist ministers who chose their site because Lima was willing to raise the most money to support the new school. There, in what had only recently been wilderness, the ministers constructed a Greek Revival academy building. The institution they founded was committed to the education of "persons of any race or color, whether male or female." The inaugural student body consisted of four men and one woman. |

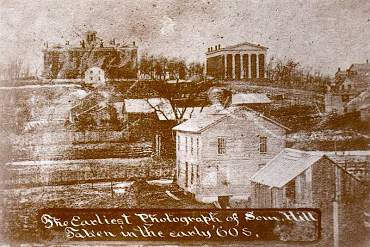

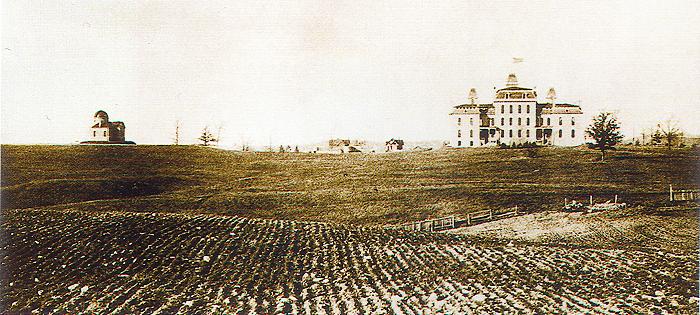

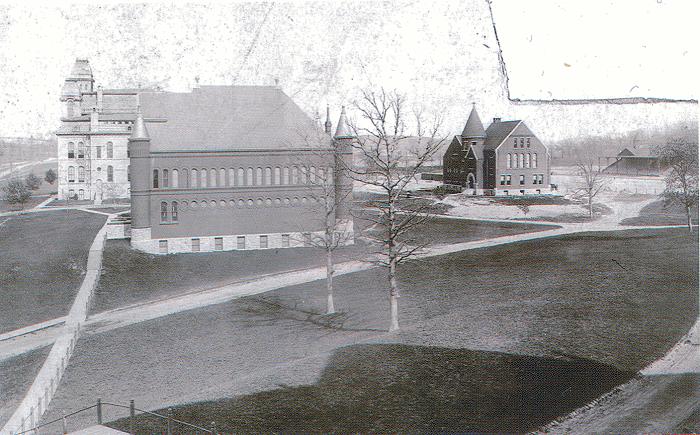

The Hall of Languages from University Place, circa 1873 In selecting a site and seeding it with the college's first buildings, the founders of Syracuse University exerted a profound influence upon the campus yet to come. Both the initial act and the development which followed allow Syracuse University to serve as an archetype of the American university campus. Likewise, the nineteenth century city of Syracuse was a classic specimen of the American urban development phenomenon. Less than fifty years had passed since the arrival of the transportation infrastructure which made the city blossom: first a canal, then a railroad. By the 1870's, this city, which had been swamp land only a half-century earlier, set out to clothe itself with the appropriate cultural infrastructure – including a nascent university. Like so many other American colleges of the time, the University was housed in a single broad and tall building set on the urban periphery, on a hilltop farm overlooking the town as if from a citadel. Many of the University's volunteer trustees were wealthy business leaders; they combined active philanthropy with economic self-interest, and real estate development figured large among their concerns. From the very beginning, the University's evolution was closely tied to that of the city, and particularly, to that of the neighborhood in which it was placed.

| |

Genesee Wesleyan Seminary, left, Genesee College Hall, right, Lima, New York, circa 1860 |

Like many other fledgling academic institutions in the nineteenth century, Genesee Wesleyan Seminary's ambitions outstripped its resources. Its difficulties were compounded by the next set of technological changes: the railroad that displaced the Erie Canal as the region's economic engine bypassed Lima completely. The Seminary created a companion college – Genesee College – in 1849, but its fortunes did not improve. In 1866, after several hard years, the trustees of the struggling college decided to seek a locale whose economic and transportation advantages could provide a better base of support.

As Genesee College began looking for a new home, the bustling community of Syracuse, ninety miles to the east, was engaged in a search of its own. The rail age had expanded the prosperity brought by the Erie Canal, and the city was booming, but its citizens yearned for something more. "What gives to Oxford and Cambridge, England, to Edinburgh, Scotland, to New Haven, Connecticut, their most illustrious names abroad?" asked one local writer. "Their Universities," he answered. "Syracuse has all the advantages: business, social, and religious – let her add the educational and she adds to her reputation, her desirability." Thus inspired, the people of Syracuse competed for the right to become Genesee College's new home. In 1869, the city was selected and, after a year of political rancor, Genesee College was supplanted by Syracuse University.

|

From

left to right: Holden Observatory, von Ranke Library (incomplete) and the Hall of Languages, circa 1887.

From left to right: The Hall of Languages, von Ranke Library

(now Tolley Administration Building), and Crouse College, circa 1889. |

George F. Comstock, a member of the new University's Board of Trustees, had offered the school, as part of the negotiations that brought it to Syracuse, fifty acres of farmland on a hillside to the southeast of the city center. In January of 1871, Reverend Jesse Peck, the first chairman of the Board of Trustees, described what was, in effect, the University's first master plan: a scheme for the construction of seven new buildings on Comstock's hillside, each to be dedicated to a different academic discipline. Peck's vision for the new campus was one of stylistic eclecticism; on one occasion, he declared that the new university should "demonstrate the perfect harmony and indissoluble oneness of all that is valuable in the old and the new."

THE EARLY YEARS

Classes met in a downtown Syracuse commercial block while the first structure built under Peck's plan, the Hall of Languages, was constructed at the summit of University Avenue. Nationally renowned Syracuse architect Horatio Nelson White was the designer of the French Second Empire structure. Upon the building's completion in 1873, the fledgling institution's students and faculty marched from downtown to their new home on the hill. The Hall of Languages stood as the only manifestation of the University's first campus plan for a long time. The Panic of 1873 interrupted the institution's further development, and the Hall of Languages housed the entire University for fourteen years. While the Hall of Languages was being built on his old property, George Comstock purchased 200 acres of the Stevens farm to the north of University Place. By 1872, Comstock had deeded Walnut Park, the centerpiece of his new "Highlands" subdivision, to the City, and successfully parceled out residential lots to the local elite. This greensward, extending northward from University Place, was soon bordered on both sides by large and gracious homes. From the beginning, Comstock intended Syracuse University and the Highlands to develop as an integrated whole; a contemporary account described the latter as "a beautiful town...springing up on the hillside and a community of refined and cultivated membership...established near the spot which will soon be the center of a great and beneficent educational institution."

|

Von Ranke Library in the foreground, with the Hall of

Languages and the Gymnasium behind, circa 1895.

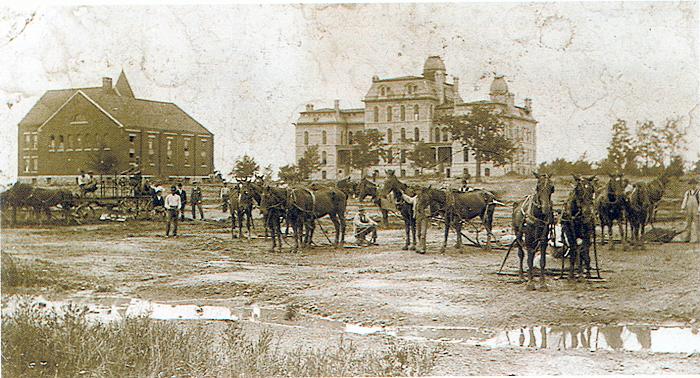

Grading the Old Oval behind the Gynasium and the Hall of

Languages, circa 1895. |

By the end of the 1880's, the University had resumed construction on the south side of University Place. Holden Observatory (1887) was followed by two Romanesque Revival buildings

– von Ranke Library (1889), now Tolley Administration Building, and Crouse College (1889). Together with the Hall of Languages, these first buildings formed the basis for the "Old Row," a grouping which, along with its companion Lawn, established one of Syracuse's most enduring images. The emphatically linear organization of these buildings along the brow of the hill follows a tradition of American campus planning which dates to the construction of the "Yale Row" in the 1790's. At Syracuse, the Old Row continued to provide the framework for its growth well into the twentieth century. The first exception to the linear development pattern was the placement of the Gymnasium (1891) in the hayfield behind the Hall of Languages. At the same time, a portion of that open land was graded and placed into service as an athletic field, together with a vegetable garden for the faculty. Loosely framed by buildings on two sides, the "Old Oval," as the field was known, joined the Lawn as a campus open space. The Oval's modest beginnings belied its later significance to the University's physical development. Seven years later, the construction of Steele Hall (1898), the University's first science building, gave definition to another new open space, located to the west of the Gymnasium and to the south of Crouse College.

1906 MASTER PLAN While the construction of Smith Hall (1902) for the College of Applied Sciences reinforced the development of the Old Row, another planning concept was undertaken with the construction of Winchell Hall (1900) and Haven Hall (1904), the University's first dormitories. These two buildings were placed on the north side of University Place, bookending the University Avenue axis leading down the hill from the Hall of Languages. Not only did the two dormitories mark the first time that campus buildings formally crossed University Place, they also marked the beginning of a romance with Beaux Arts planning principles which the University would continue during the coming decades.

The University's exponential physical growth during this period led the administration to consider a new planning effort. In 1906, after several initial attempts, including a 1905 competition among alumni architects sponsored by the Onondagan, a scheme developed by School of Architecture professors Frederick Revels and Earl Hallenbeck was adopted for the campus.

|

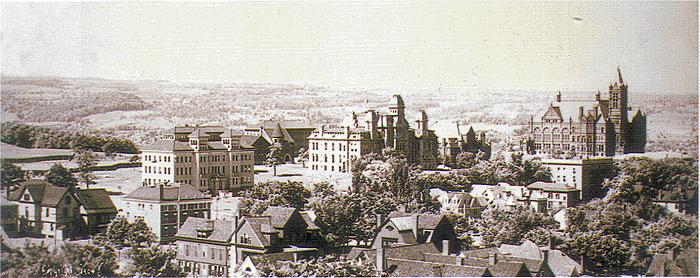

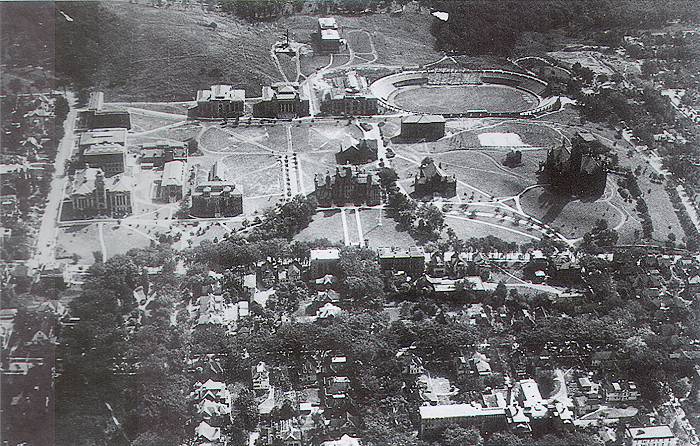

Campus as viewed from the northeast, from left to right along

the Lawn; Smith Hall, the Hall of Languages, the Gymnasium, von Ranke

Library and Crouse College, circa 1903.

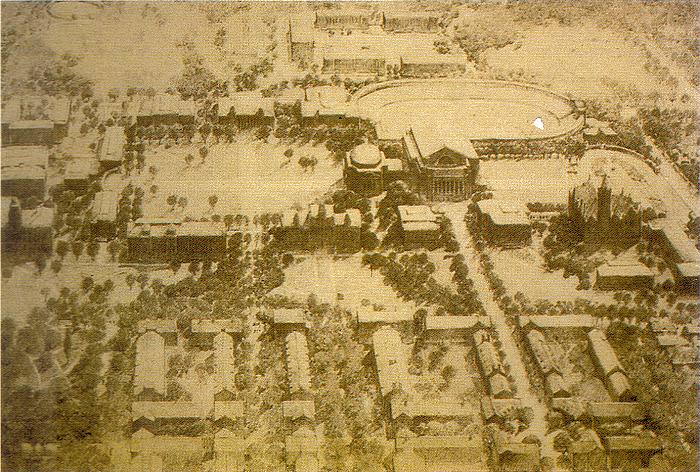

Aerial perspective of the Revels and Hallenbeck 1906 campus

plan. Note the two dormitories, Winchell and Haven Halls, at the

intersection of University Avenue and University Place -- the first two

university buildings to the north of University Place. Both were

subsequently demolished. |

The Revels-Hallenbeck plan focused on the Old Oval, proposing that the field be defined on its south side by a new range of buildings set parallel to the Old Row. Revels and Hallenbeck sited a stadium in a shallow ravine to the west of the new range of buildings, freeing the Old Oval to become a ceremonial green space. The plan's most remarkable feature was a domed addition to the rear of the Hall of Languages. This accretion, intended to contain an assembly hall, would have remade the University's first building as the north wing of a massive structure extending southward along the edge of the Old Oval. The proposed addition, which would have necessitated demolishing the Gymnasium, would have reshaped the Oval into two formal open spaces set perpendicular to one another and together forming an "L." Their "Great Quadrangle," organized along a north-south axis, was to join a smaller open space to the south of the Hall of Languages addition. Revels and Hallenbeck's scheme also marked the first appearance of the idea to relocate Holden Observatory

– in this instance, to Mount Olympus – so that the open space bounded on the north by von Ranke Library, Crouse College, and Steele Hall could be better defined.

Chancellor James Roscoe Day embraced the 1906 plan, and

Revels and Hallenbeck were commissioned to design the

Carnegie Library (1907), Bowne Hall (1907), Sims Hall

(1907), Archbold Stadium (1908), and Archbold Gymnasium

(1909), quickly completing the south side of the new "Great

Quadrangle." Meanwhile, the distinctive tower of Lyman Hall

(1907), together with Machinery Hall (1907), rose above the

Lawn, emphatically punctuating the extension of the Old Row.

Soon after, however, the University was financially

overextended. Construction stopped, with no additional

development occurring until Slocum Hall was built for the

College of Agriculture in 1918. The leviathan addition to

the Hall of Languages was never built, and the Oval became a

single quadrangle, rather than the two perpendicular open

spaces that were originally proposed.

Perhaps the 1906 plan's most lasting effect was the

reinforcement of the campus' two seminal open spaces. It

transformed and formalized the Oval, creating a Main

Quadrangle that would serve as a new organizing feature for

the campus. The plan also called for the eastward extension

of the Old Rowand the Lawn, siting a new generation of

buildings along the crest of the hill.

|

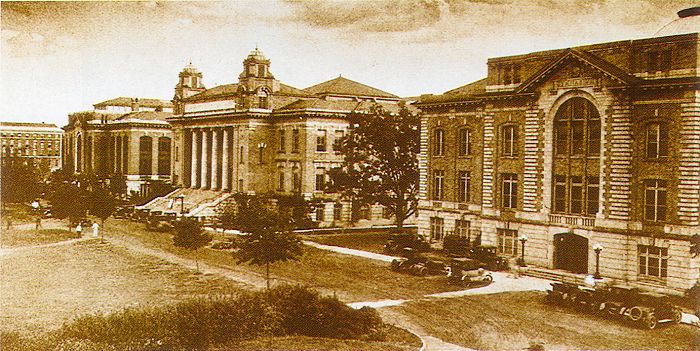

From left to right, the Women's Gymnasium, Bowne

Hall, Carnegie Library, Steele Hall, Holden

Observatory, circa 1910.

From left to right, Bowne Hall, Carnegie

library, Archbold Gymnasium. |

In a variety of ways, the 1906 plan represented a

surprisingly loose interpretation of Beaux Arts campus

design principles. While Revels and Hallenbeck had the

opportunity to design most of the resulting buildings,

their individual designs were not entirely subordinated

to an overall architectural vision. The University's

penchant for eclecticism defied the architectural

conventions of the time and, given the prevailing

trends, the critics were unsparing. Montgomery Schuyler,

writing for The Architectural Record, made the following

observations about Syracuse's campus in 1911:

"Here was ample room to layout a collection of

buildings which should have an effect of unity in the

aggregate, together with whatever variety their varying

purposes might invite or permit in detail. And seemingly

there has been enough money spent on buildings to

execute such a scheme handsomely and impressively. The

actual result is simply deplorable in the crudity of the

parts and the absence of anything that can be decently

called a whole. There is, it seems, a course of

architecture at Syracuse, which will jail of its purpose

unless it inculcates upon its students the primary

necessity of refraining from doing anything like the

buildings of the campus. "

1928 MASTER PLAN The next comprehensive campus design effort occurred during the late 1920's when the University engaged New York City architects

John Russell Pope and

Dwight James Baum for a new “general plan.” The choice of architects presaged the type of plan this was intended to be: Pope designed many of the buildings which have come, through their robust commitment to classicism and strong axial organization, to typify Official Washington, DC; while Baum, a graduate of the Syracuse architecture program, was known as a champion of Georgian Revival residential design. Together, they developed a plan that used Beaux Arts planning principles and Georgian Revival styling to shape the campus and extend it into the neighborhoods beyond. Pope and Baum's unified vision for the campus consciously rejected the eclecticism that had been the campus hallmark to date. Like most other campus plans of its generation, it was an ambitious attempt to shape an aesthetically and organizationally coherent physical environment.

|

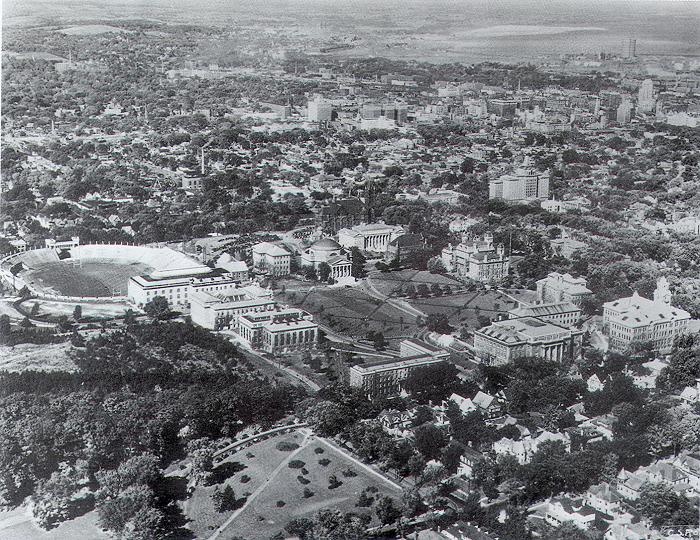

Aerial photograph of the

North Campus in the late 1920s

Aerial perspective rendering

of Pope and Baum's campus plan, showing the

proposed auditorium building attached to

Hendricks Chapel, and introducing the idea

of a new axis extending northward across the

Lawn into the residential portion of

University Hill. |

Taking the existing campus as a point of departure, Pope and Baum defined five distinct building "groups" – the Academic Group, the Men's Dormitories, the Women's Dormitories, the Medical Group, and the College of Forestry – which would be joined to one another with axial paths and streets. As their scheme's centerpiece, the architects resurrected an idea from the 1906 Plan: a very large assembly building to serve as a new focal point for the academic core. They struck a new east-west axis through the two existing quadrangles and placed a new structure at its heart. This building, which would require the relocation of the Old Gymnasium, was to be comprised of two distinct components: an east-facing chapel and a west-facing 6,000-seat assembly hall. The plan bounded the eastern edge of the Main Quadrangle with new structures, squaring it to create a well-defined central green space, 600 feet to a side. To the west of the assembly hall, the architects suggested a monumental stairway spilling down the steep hillside, flanked by new buildings aligned with the Old Row, and creating an imposing symbolic gateway to the University from Irving Avenue. While Pope and Baum showed a great deal of interest in the east-west "quadrangle" axis, they also developed multiple north-south axes that extended across the Lawn, joining the Old Row to the two proposed dormitory precincts sited on the north side of University Place. These north-south axes, stitching the campus into the surrounding urban fabric, would emerge as one of the plan's most compelling planning legacies. The 1928 Pope-Baum plan was the most detailed and comprehensive campus plan ever attempted by the University. Unfortunately, less than a year later, the Great Depression brought a rude end to the genteel social and economic circumstances that enabled institutions to pursue physical visions of a well ordered future. While Hendricks Chapel was constructed in 1930, its companion assembly hall never materialized. Fragments of the Academic, Medical, and Forestry Groups were built, while both Dormitory Groups remained on paper. The great stair from Irving Avenue, envisioned by Pope as the University's new western gateway, was never constructed. University Avenue continued to serve as the traditional approach to the Hill.

|

Aerial view of the campus

looking northwest, circa 1940.

|

To the north of University Place, the Highlands neighborhood was continuing to evolve. Its reign as a desirable residential district was short lived; after 1900, fraternities and sororities relocating from Irving Avenue gradually supplanted the original householders. In 1915, University benefactor John Archbold purchased the William Nottingham estate, on the hillside above Walnut Park, for use as the Chancellor's residence. The Roaring Twenties – a good time for the "Greek" system – led many fraternities and sororities, flush with money, to build grand new chapter houses around the perimeter of that same city park. By the opening of World War II, Walnut Park had become a Syracuse University precinct by default. After World War II, when Syracuse began to build again, it did so to accommodate a postwar enrollment explosion. The sweeping Beaux Arts visions of the nation's leading campus designers, presented so optimistically two decades before, would be abandoned as the University struggled to meet the new realities of higher education in America.

THE DEPRESSION, WORLD WAR II, AND THE MID-CENTURY Prior to World War II, Syracuse University was a small sectarian institution with ample property to accommodate its physical needs, but few financial resources. The postwar University was a different place. Higher education had been democratized: more than ever before, Americans from diverse economic backgrounds now had the opportunity to attend college. In the vanguard of this new era were thousands of veterans, aided by the GI Bill, who were preparing to resume their interrupted lives. For Syracuse University, shaking off the effects of prior debt, depression, and war, the postwar surge in college enrollment represented an opportunity for institutional transformation. New York State was unusual among large industrialized states because it lacked a strong public "land-grant" university system. Guided by Chancellor William P. Tolley, Syracuse stepped aggressively into the breach and absorbed the flood of new students, quickly doubling enrollment to 15,000 by 1948. The University’s postwar planners worked under extreme pressure, their vision of the future fueled by enrollment figures growing on a seemingly endless upward trajectory. In retrospect, they made a number of political and planning mistakes. Today, as the University seeks to recover the coherence, if not the compact size, of the pre-1930's campus, it is appropriate too understand what went wrong during those heady postwar years. At first, financial constraints precluded permanent expansion of the physical plant. Instead, immediate space needs were met by the acquisition of hundreds of military surplus prefabricated buildings. The land behind Hendricks Chapel filled rapidly with prefabricated huts intended for academic use, while temporary residential cities rose at what is now the Manley Field House area and on the grounds of the University Farm at Skytop. A prefabricated dining hall called the "Quonseteria" became the new development's centerpiece. It was an inauspicious beginning to the school's greatest period of expansion, but the University soon achieved a level of financial stability that allowed it to consider a new building campaign commensurate with the institution's newfound size and status. In 1948, Landscape Architecture Professor Noreda Rotunno created the first of several plans intended to accommodate the University's exponential population growth. Rotunno planned an "inner liner" of buildings along the south side of the Old Row, creating a narrowed "Natural Science Quadrangle" on the site of the former Old Oval. The smaller open space behind Hendricks Chapel formalized a companion social sciences quadrangle, which was to be terminated with two new buildings framing a view across the city to the west. To house the increased student population, Rotunno also projected a dormitory group for Mount Olympus, along with several new residence halls sited to the east and north of the campus core.

|

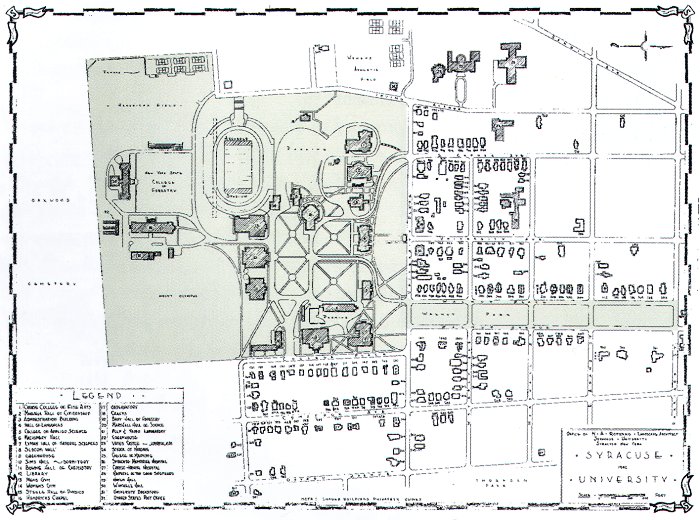

Campus Plan prepared by

Professor Noreda Rotunno in 1942: This

drawing shows the campus as it existed

at the time Rotunno commenced his

planning work. The green tone has been

added to illustrate the relationship

between the original campus and Walnut

Park. |

Unlike prior campus planners, Rotunno was able to see much of his work materialize, and the first fruits of the building campaign enjoyed local acclaim. After calling the University's existing campus "the classic example of hodge-podge in architecture," the Syracuse Post-Standard declared that Rotunno's work showed Syracuse was "at last, after its nearly 80 years, developing an architectural pattern." The first of Rotunno's bookend buildings for the social science quadrangle, the E.I. White College of Law, was completed in 1954. Construction of the first of the "liner" buildings, Hinds Hall (1955), H.B. Crouse Hall (1961), and Link Hall (1965), continued to reduce the size of the Main Quadrangle. Old gave way to new without sentimentality; the Old Gymnasium, which had been moved in 1928 to a site between Steele Hall and Archbold Stadium to accommodate the construction of Hendricks Chapel, was subsequently demolished in 1965 to make way for a new Physics Building. The University's continuing space needs, however, could not be met within the traditional campus boundaries, and it was soon expanding into the neighborhoods along the campus periphery. Beyond the campus core, new buildings rose: Shaw Dormitory (1952), Lowe Art Center (1952), the Women's Building (1953), and the Hoople Special Education building (1953). As a residential complex crowned the top of Mount Olympus, a new cluster of dormitories – Watson Hall (1954), Marion Hall (1954), DellPlain Hall (1961), and Booth Hall (1963) – was constructed along the eastern portion of University Hill, the latter facing Thornden Park, where gracious homes once enjoyed commanding views. The University also began to build major academic buildings to the north of the Lawn, with I.M. Pei's Newhouse School (1964) being the most dramatic manifestation of this new era.

The Newhouse School,

Syracuse University's most highly

acclaimed example of modern

architecture, was designed by the

internationally recognized architect I.M.

Pei in 1964. |

The campus' physical expansion coincided with the heyday of urban renewal in the City of Syracuse. For the University, the urban renewal process and its companion state and federal funding streams could not have come at a more opportune time. As one of the urban renewal plan's primary beneficiaries, the institution obtained a canvas suitable for its ambitions. It set about preparing that canvas, acquiring residential and commercial properties as part of a plan to expand the University northward as far as Erie Boulevard. Simultaneously, the urban renewal effort essentially erased the low-income neighborhood known as "the Ward," situated between the University, the hospitals, and downtown Syracuse. The Ward was replaced by an elevated highway right-of-way, public housing projects, commercial buildings, and new facilities for the growing medical complex along Irving Avenue and East Adams Street. Further inspired by visions of seemingly limitless growth, and empowered by the mandate to modernize, the University, the City, and the hospitals were remaking the face and character of University Hill. This process reached its apogee in 1966 with the unveiling of a University Hill General Neighborhood Renewal Plan, authored by Professor Rotunno. Conceived in the modernist spirit of contemporaneous New York State developments such as Albany's SUNY campus and that city's Empire State Plaza, the plan proposed an expanded series of quadrangles, set into a landscape radically remade to accommodate the automobile. The plan included expressway ramps leading directly into plinth-like underground parking garages with new groups of residential and academic towers built atop the parking plinths as far north as East Adams Street. The proposed changes included the extension of Walnut Park northward to Harrison Street and a three-sided East Quadrangle along College Place, opposite Slocum Hall. This last idea was ultimately realized, in modified form, with the construction of the Center for Science and Technology.

Bird library, built in

1972, blocked Walnut Park's green axis

into campus. It makes strong stylistic

references to Pei's Newhouse School

building, although it is much larger in

scale and less refined in detail. |

Ultimately, however, in the accelerated rush to build, short-term pragmatism often preempted long-range planning as a guide to the physical development of the campus, resulting in significant departures from the 1966 University Hill Plan. The most significant was the building of Bird Library in 1972 on the southernmost block of Walnut Park. The new library, intended to signal Syracuse's emergence as a major research institution, forever altered the relationship between Walnut Park and the Lawn. The University continued to acquire and demolish buildings in the surrounding neighborhoods, transforming entire blocks into surface lots to meet immediate parking needs. Other buildings were acquired as part of the University's land-banking activities, in the expectation that they would eventually be replaced by new construction. Like many older structures on campus, these buildings were allowed to gradually deteriorate. The staggering scope of the 1966 University Hill Plan and its predecessors, together with the construction and clearance facilitated by these plans, was driven by a mistaken belief that the enrollment growth of the postwar years would proceed indefinitely. That assumption would continue to inspire new development, even as local residents and students began to protest against the impact of urban renewal and institutional expansion. However, by the time Bird Library and Newhouse II (1973) were complete, this era of growth would be over.

THE TWENTY-YEAR PLAN

By the time Chancellor Melvin A. Eggers took office in 1971, it was clear that demographic conditions could no longer power continuous enrollment growth. Making matters worse, inflation, energy costs, and disaffection with higher education had all been on the rise. Having planned for an ever-expanding future, the University now adopted a policy of retrenchment in order to accommodate its newly diminished horizons. Unable to build anew as envisioned during the postwar era, and constrained by an uncertain financial position, Syracuse faced the need to attract students despite the marginal condition of much of its physical plant. As a result, the University turned its focus to maintaining the viability of its existing buildings. Thus began an era of strategic reinvestment, of reinforcing the functional adequacy of the physical campus. Investments were made in energy conservation, life-safety improvements, building rehabilitation, and other modest changes that would ensure the long-term viability of the University's existing infrastructure and past capital investments.

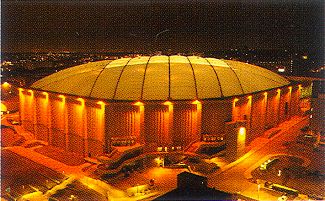

Carrier Dome |

While this period saw the construction of the Carrier Dome (1980), it was also significant for the emergence of a new ethos: that of preservation, as most notably embodied by the rehabilitation of the Hall of Languages. That project, small though it was in comparison to the great dome, represented a dramatic shift in attitudes. Thenceforth, the University would consistently look to the past as an integral part of its planning for the future. Eventually, a strategic plan was developed that included new construction. At its base, this planning effort clearly understood the importance of balancing two conflicting requirements: the need to enhance and strengthen the University's academic programs; and the need to reconcile capital and current year financial resources. This plan, ultimately referred to as the Twenty-Year Plan, sought to add new construction in order to eliminate dependence on the inefficient and marginal buildings acquired during the prewar period, and to reduce the utilization density of the existing permanent buildings while maximizing their functional adequacy. New buildings, such as the Crouse-Hinds School of Management building (1983) and Schine Student Center (1985) were now accompanied by projects bringing new life to old buildings. The former University Hospital and Steele, Smith, and Lyman Halls were renovated, and the Administration Building and Crouse College were restored to their original splendor.

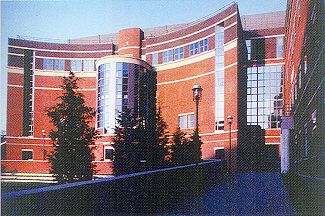

West elevation of the

Center for Science and Technology: This

pavilion occupies the southern end of

the complex's first construction phase.

Axially facing Slocum Hall, this facade

is intended to anchor a formal outdoor

court whose completion is planned for

later phases. |

Respect for the past was also accompanied by a newfound interest in urban context and the shaping of open space. These attitudes were evident in the development of the Center for Science and Technology (Sci-Tech) in 1988. This massive complex effectively shifted the core campus' boundaries one block to the east. While Sci-tech was planned as the first stage of a larger research complex, its first phase carefully defined the edge of College Place, establishing the open space sited opposite Slocum Hall's east portico. This concept had originally been proposed in the Rotunno plans. Sci-tech's design took pains to encourage east-west pedestrian movement across its site and into the Main Quadrangle, linking the student housing to the east with the core campus. The University also built upon the legacy of the Revels-Hallenbeck Plan. Sims Hall, the former dormitory building dating from that era, was strengthened with the addition of an imposing new corner entrance. Shaffer Art Building, the new home of the University's studio arts programs, was added to the Sims complex. Its round entrance was designed to strengthen the Main Quadrangle. Similarly, the College of Law library addition marked the far corner of the West Quadrangle. These projects signaled the beginning of a new commitment to the University's original campus. During this time, a seemingly mundane zoning tool called the Planned Institutional District (PID) emerged as an important factor in shaping the campus. Unlike traditional zoning, which regulates the individual land parcel, the PID concept bundles properties into districts, allowing development requirements to be met over larger areas. For example, traditional zoning may require the provision of a certain number of parking spaces on a specific development site. In contrast, the PID would allow those parking spaces to be provided elsewhere within the site's district. In effect, the PID codifies the zoning code's recognition that an institution functions as a single entity, even if it occupies multiple buildings and non-contiguous properties.

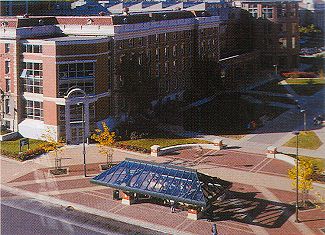

Sims Hall's new corner

entrance facing College Place: The bus

shelter at this location is a major

circulation node with convenient access

to the Main Quadrangle to the west. |

Syracuse University's PID was developed, in part, to remediate the effects of the University's postwar expansion, and the increasing public conflict regarding land use. Throughout much of the twentieth century, traditional zoning ordinances treated colleges and universities as public schools. This was significant, because public schools were allowable uses in even the most restrictive residential zoning districts. Over time, it became difficult for traditional zoning parameters to accommodate changing institutional land use patterns. Traditional zoning regarded the campus as a collection of discrete parcels, even though the campus functioned as a single entity. To correct this, the University sought to establish a PID governing the development of the campus core. This district covered an area extending from Waverly Avenue south to Oakwood Cemetery, and from College Place west to Irving Avenue. In 1967, the City approved the creation of the University Planned Institutional District. By encouraging the University to plan its campus as a series of districts, rather than as a collection of individual projects, the PID regulations facilitated planners' efforts to build a coherent campus. Therefore, during the 1980's the PID regulations would feature prominently in the University's efforts to develop a new comprehensive land use plan, one that could build sensitively upon the legacies of past campus plans and building campaigns.

"The photographs and text on this

page are provided by permission of Syracuse

University from Syracuse University Campus Plan 2003, Syracuse University Office of Design and Construction:

Virginia Denton, Director; Bohlin Cywinski Jackson; Frank W. Grauman, AIA; Theresa Ward Thomas, AIA; Karen L. Scott, RA; Larry Newman, Urban Workshop. @ 2003 by Syracuse University.

All rights reserved. No endorsement or approval by

Syracuse University is expressed or implied.

|

|

|